By Umaru Fofana

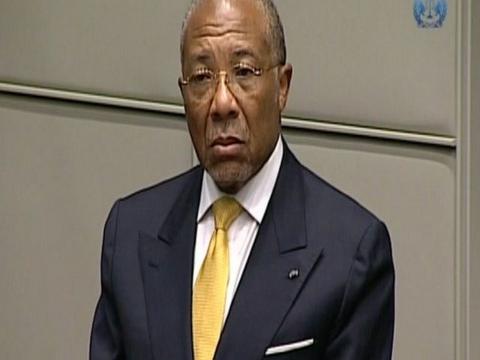

Kadiatu Fofanah died without her legs. She lost them after rebels had rained bullets on her. Without immediate medical attention due to the remoteness of her home in the north of the country and the raging war in 1998/99 she had to wait for days to reach Freetown to get even the most basic of medical interventions. Her legs had gone bad. They had to be amputated. Since that day the future of her children was blighted by the presence of her plight. Her future ceased to exist. Her life was seized by deprivation. Her human dignity sized down. I last met Kadiatu a few years ago in the outskirts of Freetown. She was confined to a wheelchair where she would sit for the whole day for the rest of her life. In her new home at the Grafton settlement built by Norwegians for amputees and war wounded, she struggled for her daily bread. Like she did to educate her children. Like did most of the hundreds of others who had their arms and limps hacked off by rebels during Sierra Leone’s war in the 1990s, Kadiatu had to beg on the streets to feed and to be able to tend to her family. Children defined by the agony of their mother. Children scorned by society for the misfortune of their mother. Children with no dependable shoulder to lie on, because of the predicament of their mother. Their future rendered bleak at best, if not nonexistent. Dozens of women were raped by rebels and later abandoned by their husbands by no fault of theirs. Some are still grappling with the attendant medical conditions. Children were turned into victims by being trained and turned into rapists, and used as perpetrators to unleash mayhem on mostly innocent people. True to the saying by the Nobel laureate, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, “it is a shame that adults should expect children to fight their wars for them”. But 11 years since that war ended does anyone care to ask how much child abuse still goes on today, some by public officials who should be protecting these girls. The end of the war, many erroneously think, meant the end of the sexual exploitation of girls. How wrong! And what have we really done to tend to those exploited during the war. The stigma has led to their loss of self-confidence and even their humanity; consequently they have all dropped out without a social safety net for them. Kadiatu died an angry woman. She died a frustrated mother. She died feeling neglected by society and abandoned by successive governments who failed to provide for her and her children their most basic needs, including those who pumped millions of dollars into the trial of Charles Taylor. It was for atrocities like those visited upon Kadiatu that the whole world went wild and almost came to a standstill last week ahead of the final decision by the Appeals Chamber of the United Nations-backed Special Court for Sierra Leone. That decision was whether to uphold or scale down or even increase the decision of the trial chamber in the case of the former Liberian president Charles Taylor. I subscribe to Google Alert for a few countries including, obviously, Sierra Leone. So my email was on overdrive with all sorts of websites in all sorts of countries with all sorts of headlines mentioning the name of the country and Charles Taylor. Why not? Among many other firsts, he is the first former head of state to have been indicted and convicted by a war crimes court. The world wants us to believe that the conviction of Mr Taylor would serve as a deterrent to leaders who think their country and the lives of the people are in their hands and they can do whatever suits them. How wrong! Even with Taylor being tried there were and still are leaders and warlords busy doing those things he is being punished for. Darfur, Nigeria, Somalia, etc. There are still leaders who use the police and the army as weapons of terror to unleash carnage against defenceless civilians who stand between them and political power. Zimbabwe, Guinea, Sudan and even Sierra Leone to some extent. You need look no further or farther to see that being perpetuated. Some leaders, or leaders of some sort, use their nation’s natural resources against the people. You must be blind to think that the commission of atrocities stopped with the arrest and conviction of Taylor. But with Taylor’s 50 year jail term upheld by the appeals court, his chapter is more or less closed as he heads almost certainly to a prison in England. But the closure of that chapter should open that of the victims of that war he has been convicted for. Thirteen years after she had been crippled, Kadiatu died utterly destitute. She left behind her offspring with no individual or institution to help care for them. Last year several amputees and other victims died largely of their wounds emanating from societal neglect. It is perhaps not worth celebrating the half a century prison term for Mr Taylor when the victims of his carnage litter the streets of Sierra Leone hopelessly. If she were alive today Kadiatu would be weeping more sobbingly at the sentencing of Taylor than she did when I first met him. Not so much because she would have felt sorry for him as for the loss his involvement caused her. Effectively it means the life of the Special Court has ended with the end of the life of Taylor in freedom. Do not get me wrong, the trial of Taylor and the other ringleaders of the war is a great step. Although it is regrettable that some others who committed heinous crimes were let go of simply because they did not “bear the greatest responsibility”. An alternative justice mechanism should have been devised to bring justice to bear on them. Even more regrettable is the fact that the victims have been left to lurk in squalor. Convicted and sentenced for crimes he committed that left tens of thousands killed and maimed, the question persists “what happens to Taylor’s victims?” The Special Court spent hundreds of millions in its less than ten years of operation. Many have become rich because of its setting-up. Their children attend some of the best schools. They have built houses. Deservedly, of course. But so do victims of the carnage deserve better than they are currently getting, if they are getting anything at all. Kadiatu’s children languish in an amputee camp. So do the hundreds of other war victims and their children. They must be a scar on the consciences of our government and all those foreign governments who donated all the huge sums of money towards the cause of our war crimes court. That help will be incomplete if the abandoned victims and their families, who are dead in all but name, are not resurrected. The best way to immortalise the good work of the Special Court for Sierra Leone is to pursue as vigorously as they did with the court, addressing the welfare needs of the victims of the war that set up the court. I hope someone is listening. (C) Politico 01/10/13