By Kemo Cham

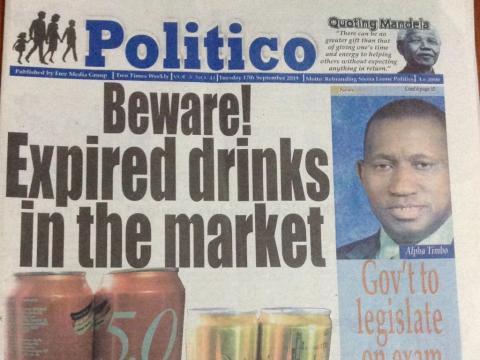

As you would expect, if you were part of our line of work, on September 17 we were inundated with calls in the newsroom, thanks to our lead front page story – ‘Beware! Expired drinks in the market.’

This story was the result of three weeks of investigation. It took sheer hard work and commitment to grind out a story like this one.

Politico’s investigation uncovered the existence of two brands of expired products: Sting, an energy drink, and 5,0 Original, an alcoholic drink. According to samples in our possession, both products expired since last July. The expiry date between the two products is just 12 days apart.

So, among the calls we received, two stood out. They were from two separate business entities that claimed they were importers of the two brands.

The first call came from a man claiming to represent Pee Cee and Sons Limited. According to the caller *(name withheld), who introduced himself as the Public Relations Officer, they were one of multiple companies that import Sting. And he swore that their own products were not due to expire until November.

This account by itself provokes a whole new line of questioning for a future investigation. For a start we should all be worried now about how many batches of expired Sting drinks are on the market.

The Pee Cee representative was therefore concerned that our report would prove damaging for their business since we had reported that Sting energy drink had expired. Curiously, he also claimed that officials of the Ministry of Trade visited their store on the same morning of the publication and verified all his claims. He then went on to request for a proof of our report that there were expired brands of the drinks in the market.

Since we sent him a snapshot of the part of the drink carrying the manufacture and expiry date, he is yet to get back to us.

The second call came from a sales representative of a less popular business entity that said they are the sole importer of 5,0 Original. And they, like Pee Cee and Sons, also claimed that their products were not due for expiry until December. This second caller also said a team from the Ministry of Trade which visited them had verified this.

But here is the irony; as part of our investigation, we contacted the Trade Ministry on at least two occasions, and on both occasions they referred us to the Standards Bureau, which they said is the only institution in a position to provide us with the answers we sought.

When we got to the Bureau, they couldn’t provide us contact for any of the importers. Its spokesman said they didn’t have a database of importers and therefore had no idea about the identities of the importers.

Still, before we went to press, we reverted to the Trade Ministry. Our contact there demanded that we sent our queries, for onward transmission to the relevant officials. They sounded unsure though that the officials would want to comment.

We did make it clear that we were publishing the story the following day. They never got back to us.

The questions now are:

Who visited those businesses after we published the story?

If it were the Trade Ministry, how comes they were so rapid in their reaction? How did they know exactly where to go to, even though they didn’t have any idea a day earlier?

Knowing how public officials work in this country, we will be surprised if we get answers to any of these questions. We’d be happy to be surprised though.

In any case, the incident illustrates a reality about the experience we go through as journalists trying to keep you, the public, informed – the sheer indifference with which public officials treat us.

And the consequence is a dysfunctional system, as the situation this story about expired drinks depicts. Unlike other cases, what is different here is that this is about food. There is no need to stress that the seeming complicity of public authorities could put our health and even lives in danger.

In the course of our investigation, we gathered that there could be far more expired drinks and other foodstuff in the market across the country than one can imagine. And it’s not like the traders are hiding it. Perhaps they know that there is just no system in place to bother them. The thought of no proper food safety system in Sierra Leone is at the very least scary.

The samples of Sting we still have in our possession were obtained from one of many hawkers at Abacha Street. There were several of them competing for buyers. As you would expect, cheap products attract many Sierra Leoneans. Illiteracy, poverty and ignorance has fueled this situation over the years.

One hawker, a young boy, openly sold the drink under the Cotton Tree on Siaka Steven Street. We sighted sellers along Pademba Road, where a young girl was selling from a carton on her head.

The 5,0 Original samples were bought from a shop along main Congo Town Road.

Granted, like in all sectors, there are competing priorities for the Ministry of Trade. But I wonder what can be more important than safety of the food and drinks that come into the country.

In the words of its own officials, the Standards Bureau is a facade. Not only is it so grossly inadequate in its presence across the country, it also lacks the personnel and equipment to conduct basic test to certify foodstuff imported into the country.

This story has shown us that, we are all on the front lines of a possible health emergency and the authorities at the very least are not paying attention.

We can only say, watch what you eat or drink. No one else is watching for you. We are all on our own.

© 2019 Politico Online